| Home | List of Names | Family Trees | |

|

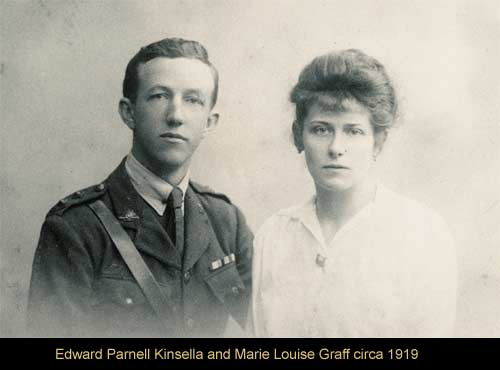

Edward Parnell KINSELLA Born: 10 June 1893 Died: 20 December 1967 Mother: Mary Jane SHANNON Father: Patrick KINSELLA Married: Marie Louise Josephine GRAFF Date: 2 August 1919, Marchienne-au-Pont, Belgium Children: Marie Patricia Germaine "Fif" KINSELLA (18 August 1920) Edward Louis "Peter" KINSELLA (1 April 1923-9 November 1997) Elizabeth Joan "Betty" KINSELLA (18 May 1926-20 April 1974) Anthony Jules "Tony" KINSELLA (4 February 1928) Brian Charles KINSELLA (10 June 1930-4 February 1941) The page of the First World War Nominal Role showing Edward Parnell Kinsella's name |  Edward Parnell Kinsella |

Edward Parnell Kinsella, 1914

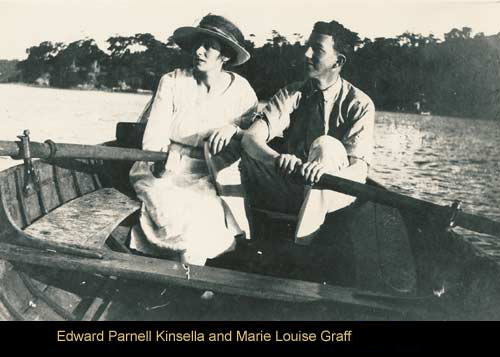

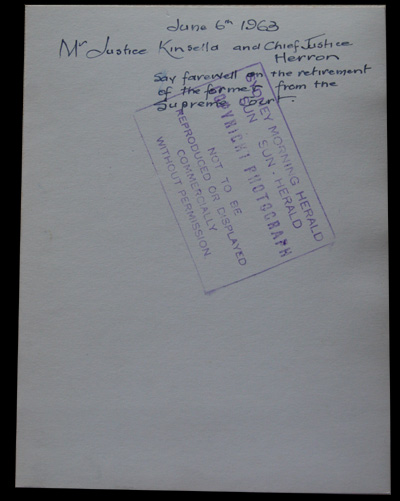

Pin use during Edward Parnell Kinsella's election campaign  Edward Parnell Kinsella's ANZAC pin, front and back  Souvenir picture from Jenolan Caves, 1922. Edward Parnell Kinsella is in the middle of the back seat.  Mr Justice Kinsella (Edward Parnell) and Chief Justice Herron, June 6th 1963  Back of the picture above  Edward Parnell Kinsella  A series of images taken by Edward Parnell Kinsella on the battlefields in Flanders, Belgium, 1917 A biography of Edward Parnell Kinsella written by his grandson, Brian Edward Kinsella: Edward Parnell Kinsella was born at Glenn Innes, in the north of New South Wales, in the winter of 1893. He was the second of six children of Patrick Kinsella, an Irish-born sheriff's officer who had immigrated to Australia during the great potato famine. He was educated at the St Patrick's College, Goulburn, and then joined the New South Wales Department of Lands as a cadet draughtsman. Between 1910 and 1914 he worked for the Department at Wagga Wagga, Moree and Glen Innes. When war broke out in 1914 in Europe he enlisted in the Australian Imperial force on 28 August, and joined the Second Battalion as a private soldier. The battalion embarked for Egypt soon afterwards and was one of the units which spearheaded the landings on Gallipoli on the 25 April 1915. He was in the third wave of boats to reach the beach on the morning of the 25th. He served there for the entire campaign, fighting some of the most memorable battles of the nine months the Australian troops spent on the peninsula. In an incident which occurred during one attack on the strong Turkish trench lines, the soldiers of his battalion had been ordered to make a frontal assault on a particular length of trench and in an attempt to prevent unnecessary casualties to their own troops from accidental discharges of their weapons. They had been ordered by their officers, in their wisdom, not to have rounds of ammunition in the breeches of their Lee-Enfield rifles, but to use bayonets only. With an admirable sense of self-preservation, Edward Kinsella and other diggers ignored this order and made sure they had one up the spout when they clambered from their own trenches and attacked. They reached the enemy trench, which was covered with logs and earth for protection from artillery fire. They threw grenades down into the trench among the Turks wherever there were apertures. Some of the Australians were able to break holes in the roof and drop through into the trench itself. My grandfather was one of those who did so, his bayonet fixed to the muzzle of his rifle and ready for close quarter combat. As he dropped he was immediately confronted by a large Turkish soldier. "He was well over six foot tall. In the confined space he looked huge. More importantly he was raising a rifle to point at me," my grandfather said later. His rifle at the ready, his bayonet was pointing at the Turk but too far from him to reach him in time. My grandfather pulled the trigger and shot him in the chest, killing him instantly. He killed another two Turks with his bayonet before the trench was won. If he had not disobeyed that order he would probably have been killed. At the end of Gallipoli campaign, my grandfather was one of the last Australians to leave the beach. By then promoted to sergeant, he was one of those who set up the final elaborate deception which allowed the withdrawal of Australian troops to be such a success on that last night. The last Australians to leave set up rifles fixed in the forward trenches with contrivances of string and jam tins containing water so that the weapons would continue to fire sporadically in the direction of the Turkish lines during the hours of darkness when in fact the Australian trenches were empty of troops. Back in Egypt, Sergeant Kinsella was transferred to the 54th Battalion and in June 1916 sailed for France in August 1916. He was commissioned in the field as a Second Lieutenant and was promoted full Lieutenant in December of that year. For two years he fought in Flanders and, like most of the troops, came close to death many times in the great battles of the war in Europe. After the war he spoke little about his personal experiences during those two years. However, he did relate one incident. He had been ordered to lead a small reconnaissance patrol from the Australian lines across no manís land towards the German trenches. It was a pitch dark and bitterly cold winter night on which he set out, carrying only a pistol as his personal sidearm, leading a group of half a dozen soldiers armed only with rifles. They crawled close to German trenches carried out the observations they were suppose to, and were heading silently back when they heard a German patrol moving near by. The Australians, not knowing the strength of the enemy, lay flat on the ground, sinking into the mud and water and remaining utterly silent. They heard the Germans moving closer and then, peering up carefully without moving a muscle, saw a line of four Germans in single file only a few feet away moving across their front. My grandfather lay perfectly still his arms out stretched in front of him with a Webley revolver grasped in his right hand. The Germans passed by so close that the officer leading them stepped with his right foot on my grandfatherís left hand, the heel of his boot grinding into the skin and flesh leaving a scar which he carried all his life. A split second later the Australians leapt up and overpowered the surprised Germans, killing them with bayonets. Any shots might have pinpointed their position and drawn machine gun fire. The Australians then returned to their own battalion lines where they found that while they had been on the patrol a German artillery shell had plunged through the roof of the battalion command post, where all the officers of the battalion, apart from my grandfather, had been having a meeting. All had been killed. Shortly after that patrol my grandfather returned to Australia for two months leave in June and July 1918. He returned to France to be posted to the 56th battalion in the following November, just in time for the Armistice. While on local leave during the war he had met a Belgian girl, Marie Louise Graff, who lived in the small town of Marchienne-au-Pont. After hostilities had ended he remained in Belgium with the army for almost a year, although during this time he also visited London on leave and toured parts of the English countryside. He and Marie Louise Graff, my grandmother, were married at the Town Hall in Marchienne-au-Pont on 2 August, 1919. Soon after the wedding the couple sailed for Australia. On his return to Sydney my grandfather went back to his old job in the Department of Lands in February in 1920. Later, he became a barrister. For time in the 1930ís he was a member of the New South Wales State Parliament, and later a judge of the Supreme Court. He died in 1967 at the age of 75. | |

| Last updated: August 1, 2009 | |